Apparently I’m late to the party but I guess hustle culture is officially dead and we can all finally relax now. The long days and nights are over! Sort of. We’re still required to sell our labor power to someone and give them all the surplus value we create, but now we can chill and just, like, take some time to find ourselves.

For those unfamiliar with hustle culture, it is (was, apparently) a corporate buzzword for a mindset that glorifies working as much as is humanly possible. It’s always being “on,” never really clocking out, always being available, grinding; neglecting health, family, and life itself, and then bragging about it. To the majority of us, this cartoonish mindset sounds like the kind of monomaniacal psychosis we would definitely like to avoid. But a certain demographic–I assume mostly a subset of professional and semi-professional entrepreneurs, especially those who aspire to be petty bourgeois–feel that “hustling” is totally rad and they want you to know.

Implicit vs. Explicit.

Fully embracing hustle culture as a fundamental life principle clearly requires absolute belief in the class mobility promised by the American Dream, but it also requires an inflated sense of belief in your own abilities and malignantly elevated levels of self-esteem. The target-customers of the business motivation and self improvement industry don’t need a label for their workaholic behavior. It’s reinforced by propaganda as blatant as this, but we are always surrounded by the more subtle forms of ideology that justify working yourself to death. It’s baked into The Core of the dogma that justifies capitalism itself, a self evident trope of the bootstrap crowd; work hard, don’t complain, be positive, and you too can get rich. Even if you don’t fully accept that premise, you still gotta live in this world that it has created. So how is “hustle culture” different from business as usual?

It’s not. “Rejecting” “hustle culture” is just the latest corporate fad in an increasingly hyper-exploited world. The term seems to have arisen out of the digital wastelands circa 2017 when backlash against an ad campaign for the company Fiverr started popping up on Twitter. Fiverr, apparently, is an Israeli gig-economy micro-outsourcing company “worth” more than 5 billion US dollars. They’re somehow more exploitative (or at least more hated) than Uber, et al. Online freelancers in graphic and product design, marketing, film, programming, and so on, post their services and purchasers bid on them. They describe themselves as a “Freelance Services Marketplace for The Lean Entrepreneur,” and have drawn derision from workers and capitalists alike for driving down service prices, providing poor quality services, etc. I mean, it’s the gig economy you created, what do you expect? I’ll just take the copyright risk and put the ad in here ’cause I’m too lazy to write some lame description of it:

The ad campaign was called In Doers We Trust. Now, I post a lot of hyperlinks, so if you didn’t click on the previous one, it’s cool, I get it. But that link is this video, which is apparently of one Fiverr’s ads from that campaign, and you should definitely click on it. Go ahead, click.

I’d like to think I’m not a complete idiot and that I can recognize satire when I see it. As much as the core of my being tells me otherwise, I can find no evidence that this ad is anything but a genuine attempt to market their site. I can see what they were going for: Youthful, hip, internet campaign to appeal to the entrepreneurial underdog, complete with edgy Millennial stuff like cuss words, sex, and bongs. They even threw in a nostalgic 80’s pop culture reference and checked the social consciousness box on the Ethical Capitalism® form by suggesting you could save endangered species with all the money you’re gonna make from their app. They styled the monologue like a badass, take-no-prisoners Glengarry Glen Ross speech and figured they’d be internet marketing legends. But, like most of us, you probably noticed the more dystopian elements suggesting that you maintain a constant state of productivity, working so hard that you ignore your own mortality and let work interrupt even your most sacred of times: fucking.

Everyone but this guy was not down with the In Doers We Trust bullshit. It was just too explicit and transparent in its embrace and celebration of capitalist misery that it entered the realm of cartoon, the realm of cheese. On the leftist and liberal sections of Twitter, Reddit, etc. the reactions were, predictably, not favorable to the ads. In early 2017, The New Yorker ran a really good piece about how the late-capitalist gig economy celebrates accepting the misery it creates as honorable, and featured the ad campaign as an example of our workaholic culture’s brutality. Somewhere around this time I forgot all about the term hustle culture, because I’m not an entrepreneur or a douchebag. At the end of the day, hustle culture is just capitalism operating as usual. Capitalists always strive to maximize the rate of exploitation.

Well, in researching stuff for some upcoming articles, I found myself googling hustle culture for some reason. It seems that by 2019 the backlash against hustle culture was so widespread that even the mainstays of the corporate world were denouncing it. Our noted anti-capitalist comrades and Friends of the Proletarian Revolution over at Entrepreneur magazine have taken to declaring hustle culture toxic to business and recommend self care, while the radical communists of Forbes, among many others, have done pretty much the same. The Wellness-Industrial Complex quickly got on board with the hustle culture hate. In fact, just google the words “hustle culture” now, or search #hustleculture on Twitter. You’ll see countless takes from management-types, health-gurus, lifestyle coaches, and mommy-bloggers, warning of hustle culture’s social harmfulness, mental toxicity, and physiological dangers. They urge us to slow down, have patience, take time for yourself, take a step back, and remember the big picture. And if you’re still worried about being a temporarily embarrassed millionaire, there’s even an AntiHUSTLE get-rich-quick book promising to teach you “Why the concept of ‘hustling’ is actually working against you and keeping you in the poor house” with a “step-by-step guide to starting a six figure business in one year.” So, like, just chill man. You just gotta relax your way to riches.

It should be plainly obvious that not having to “hustle” is simply not an option for many, many (i.e. most) people in the world. I mean, I don’t even have to look to an actual leftist source (remember folks, liberals are not leftists), let alone a Marxist one, to make this point. As Issabella Rosario, writing for the NPR podcast Code Switch points out, “The problem is, hustling still isn’t a choice for people who aren’t at the top. There’s a world of difference between staying late at the office to score a promotion and peeing in a bottle to keep your job at an Amazon warehouse.” We all know working people can’t just decide to have more “me time” because they feel burnt out from too much “hustling.” They can’t always decide to quit their second (or third) job because its “toxic.” This was the core of the real backlash against the ad campaign. But the privilege and hypocrisy of the petty bourgeoisie is so self-evident that it’s not very interesting.

What is interesting is how quickly the capitalist media latched on to the organic backlash against the hustle culture style of advertising and ran with it, in what amounts to yet another form of advertising. Since the ad campaign tried to fly too close to the sun by celebrating the acceptance of the human misery caused by capitalism as a noble virtue it obviously had to be disavowed. So, in the same way that the music industry will take the styles and aesthetics of a counterculture and sell it back to itself, homogenized, the corporate world takes the witty Twitter-dunking that followed In Doers We Trust and tries to sell you an app for mindfulness.

Although not exactly what he was talking about, it reminds me of what the great Mark Fisher wrote in Capitalist Realism about corporate anti-capitalism:

In the cases of gangster rap and Ellroy, capitalist realism takes the form of a kind of super-identification with capital at its most pitilessly predatory, but this need not be the case. In fact, capitalist realism is very far from precluding a certain anti capitalism. After all, and as Žižek has provocatively pointed out, anti-capitalism is widely disseminated in capitalism. Time after time, the villain in Hollywood films will turn out to be the ‘evil corporation’. Far from undermining capitalist realism, this gestural anti-capitalism actually reinforces it. Take Disney/Pixar’s Wall-E (2008). The film shows an earth so despoiled that human beings are no longer capable of inhabiting it. We’re left in no doubt that consumer capitalism and corporations – or rather one mega-corporation, Buy n Large – is responsible for this depredation; and when we see eventually see the human beings in offworld exile, they are infantile and obese, interacting via screen interfaces, carried around in large motorized chairs, and supping indeterminate slop from cups. What we have here is a vision of control and communication much as Jean Baudrillard understood it, in which subjugation no longer takes the form of a subordination to an extrinsic spectacle, but rather invites us to interact and participate. It seems that the cinema audience is itself the object of this satire, which prompted some right wing observers to recoil in disgust, condemning Disney/Pixar for attacking its own audience. But this kind of irony feeds rather than challenges capitalist realism. A film like Wall-E exemplifies what Robert Pfaller has called ‘interpassivity’: the film performs our anti-capitalism for us, allowing us to continue to consume with impunity. The role of capitalist ideology is not to make an explicit case for something in the way that propaganda does, but to conceal the fact that the operations of capital do not depend on any sort of subjectively assumed belief. It is impossible to conceive of fascism or Stalinism without propaganda – but capitalism can proceed perfectly well, in some ways better, without anyone making a case for it. Žižek’s counsel here remains invaluable. ‘If the concept of ideology is the classic one in which the illusion is located in knowledge’, he argues, ‘then today’s society must appear post-ideological: the prevailing ideology is that of cynicism; people no longer believe in ideological truth; they do not take ideological propositions seriously. The fundamental level of ideology, however, is not of an illusion masking the real state of things but that of an (unconscious) fantasy structuring our social reality itself. And at this level, we are of course far from being a post-ideological society. Cynical distance is just one way … to blind ourselves to the structural power of ideological fantasy: even if we do not take things seriously, even if we keep an ironical distance, we are still doing them.’

Capitalist ideology in general, Žižek maintains, consists precisely in the overvaluing of belief – in the sense of inner subjective attitude – at the expense of the beliefs we exhibit and externalize in our behavior. So long as we believe (in our hearts) that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange. According to Žižek, capitalism in general relies on this structure of disavowal. We believe that money is only a meaningless token of no intrinsic worth, yet we act as if it has a holy value. Moreover, this behavior precisely depends upon the prior disavowal – we are able to fetishize money in our actions only because we have already taken an ironic distance towards money in our heads.

So while the individual consumer privileged enough to embrace the “new” anti-hustle-culture attitude which emphasizes self care and “work/life balance” may be sincere in their wish to distance themselves from their work, it ultimately doesn’t matter. It obviously doesn’t matter for the working class, who are at the mercy of the labor markets and so on, but even for the “self-employed” hustler, it makes no difference to Capital. You’re still going to need to hustle. It’s largely performative spectacle. Who but the most fraudulent, uninteresting, and sociopathic among us doesn’t ultimately wish for a shorter working day? Again, we return to Fisher:

Corporate anti-capitalism wouldn’t matter if it could be differentiated from an authentic anti-capitalist movement. Yet, even before its momentum was stalled by the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center, the so called anti-capitalist movement seemed also to have conceded too much to capitalist realism. Since it was unable to posit a coherent alternative political-economic model to capitalism, the suspicion was that the actual aim was not to replace capitalism but to mitigate its worst excesses; and, since the form of its activities tended to be the staging of protests rather than political organization, there was a sense that the anti-capitalism movement consisted of making a series of hysterical demands which it didn’t expect to be met. Protests have formed a kind of carnivalesque background noise to capitalist realism, and the anti-capitalist protests share rather too much with hyper-corporate events like 2005’s Live 8, with their exorbitant demands that politicians legislate away poverty.

Live 8 was a strange kind of protest; a protest that everyone could agree with: who is it who actually wants poverty? And it is not that Live 8 was a ‘degraded’ form of protest. On the contrary, it was in Live 8 that the logic of the protest was revealed in its purest form. The protest impulse of the 60s posited a malevolent Father, the harbinger of a reality principle that (supposedly) cruelly and arbitrarily denies the ‘right’ to total enjoyment. This Father has unlimited access to resources, but he selfishly – and senselessly – hoards them. Yet it is not capitalism but protest itself which depends upon this figuration of the Father; and one of the successes of the current global elite has been their avoidance of identification with the figure of the hoarding Father, even though the ‘reality’ they impose on the young is substantially harsher than the conditions they protested against in the 60s. Indeed, it was of course the global elite itself – in the form of entertainers such as Richard Curtis and Bono – which organized the Live 8 event.

To reclaim a real political agency means first of all accepting our insertion at the level of desire in the remorseless meat-grinder of Capital. What is being disavowed in the abjection of evil and ignorance onto fantasmatic Others is our own complicity in planetary networks of oppression. What needs to be kept in mind is both that capitalism is a hyper-abstract impersonal structure and that it would be nothing without our co-operation. The most Gothic description of Capital is also the most accurate. Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombie-maker; but the living flesh it converts into dead labor is ours, and the zombies it makes are us. There is a sense in which it simply is the case that the political elite are our servants; the miserable service they provide from us is to launder our libidos, to obligingly re-present for us our disavowed desires as if they had nothing to do with us.

The ideological blackmail that has been in place since the original Live Aid concerts in 1985 has insisted that ‘caring individuals’ could end famine directly, without the need for any kind of political solution or systemic reorganization. It is necessary to act straight away, we were told; politics has to be suspended in the name of ethical immediacy. Bono’s Product Red brand wanted to dispense even with the philanthropic intermediary. ‘Philanthropy is like hippy music, holding hands’, Bono proclaimed. ‘Red is more like punk rock, hip hop, this should feel like hard commerce’. The point was not to offer an alternative to capitalism – on the contrary, Product Red’s ‘punk rock’ or ‘hip hop’ character consisted in its ‘realistic’ acceptance that capitalism is the only game in town. No, the aim was only to ensure that some of the proceeds of particular transactions went to good causes. The fantasy being that western consumerism, far from being intrinsically implicated in systemic global inequalities, could itself solve them. All we have to do is buy the right products.

Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: is there no alternative?

Fiverr’s subsequent ad campaigns are equally as brilliant as In Doers We Trust, by the way.

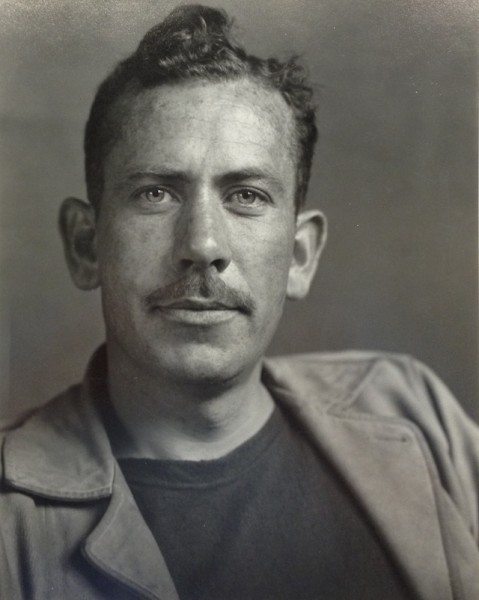

As a last note, In writing this I found out that the great quote, attributed to John Steinbeck, “Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat, but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires,” is misquoted. This is how he actually said it:

“I guess the trouble was that we didn’t have any self-admitted proletarians. Everyone was a temporarily embarrassed capitalist. Maybe the Communists so closely questioned by the investigation committees were a danger to America, but the ones I knew—at least they claimed to be Communists—couldn’t have disrupted a Sunday-school picnic. Besides they were too busy fighting among themselves.”

John Steinbeck, A Primer on the 30’s, from America and Americans

So, same sentiment.

Now, you’ll have to excuse me, I’ve got to go hustle.